According to incoming President Shirley Lashmett, Jane Freeman, Dick Freeman’s wife just died. Dick was our District President and member who raised out club to a standard of excellence, and Jane was a great supporter of Exchange.

The next meeting will feature Tom Johnson, Editor of StuNews. See page 1.

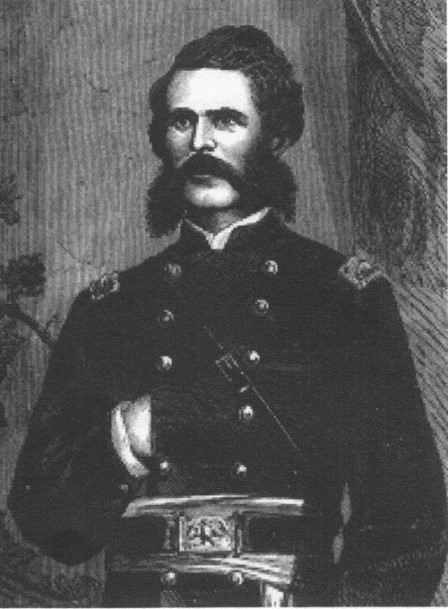

PROGRAMwas our own Bob Wood, introduced by President Ken, who said a lot of nice things about him. (Ed. Thanks, Ken.) Bob talked about his great grandfather: “The Craftiest of Men: William Patrick Wood and the Establishment of the United States Secret Service.” William P. was born the son of a diemaker in 1820 and was interested in modeling and inventions, not dies. After a frustrating youth, he joined the Army towards the end of the Mexican War, 1946-8 when Mexico was trying to take back Texas. A fearless foot soldier in the cavalry, he saw 100 men dead in one trench on his way to the battle of Chatultepec Castle, which had in it the “the halls of Montezuma.” He was the first American to speak to 25 soldiers in that grand edifice about American political and religious values.

When the war ended, he was honorably discharged and moved back to Cumberland, Maryland where he married Harriet Smith and proceeded to have one daughter and seven sons. During these years in the 1850s, William P. continued to build his skill at modeling and understanding patents associated with inventions. When there was a patent infringement case involving the McCormick reaper, he was asked to testify as an expert witness, and the attorneys involved included Ed Stanton (later to become Secretary of War) and Abraham Lincoln. Stanton got together socially with Lincoln and William P. to hear of his exploits during the war. Stanton and Wood became best friends. On one occasion, it is reported, that Lincoln hoisted Wood’s first-born son Sam “to the towering altitude of his face and kissed him on the forehead.”

William P. Wood was very pro-Union, anti-slavery, and worked with some of his old Army buddies to help train John Brown’s mini-army for the raid on Harper’s Ferry, but backed out at the last minute saying that if they were caught, they’d be killed. He was right. He was also made aware by Stanton that a large percentage of the money in circulation was counterfeit, and since there were some rewards for capturing them and their plates and dies, he jumped in and was hugely successful in capturing a large number of them and put them in the Old Capitol Prison, with Stanton’s encouragement.

William P. actually wanted to be the “Federal Marshall” of Washington (i.e., Chief of Police) but when Lincoln was elected, he gave that job to a crony of his. However, Stanton, who was now Secretary of War, stepped in and offered him the job of Superintendent of the Old Capitol Prison, which he ran during the Civil War and often helped personally capture counterfeiters to put there. Wood had the reputation of fighting hard for “good bread” for the prisoners. He personally stated, “Toward the end of the Rebellion, I had secured quite a museum of counterfeit plates…and performed the service under cover of a single letter-sheet signed by order of the Secretary of War.”

Old Capitol Prison

Old Capitol Prison

However, at the end of the War, there was still 20% “queer” money and on the very day that he was shot, Lincoln held a cabinet meeting that included this topic. Treasury Secretary Hugh McCullough was upset, saying “rewards and private detectives have proved insufficient… (we need a) …” permanent force managed by a directing head.” Lincoln is reported to have said, “Work it out your own way, Hugh. I believe you have the right idea.” After Wood had interrogated those thought to be associated with the assassination suspects, on July 2 Congress approved the creation of the Secret Service inside the Treasury Department.

For four years William Patrick Wood’s Secret Service captured dozens of counterfeiters and established six-point criteria for each Special Operative, one of which required “honesty and fidelity in all transactions” as well “on duty 24 hours a day.”

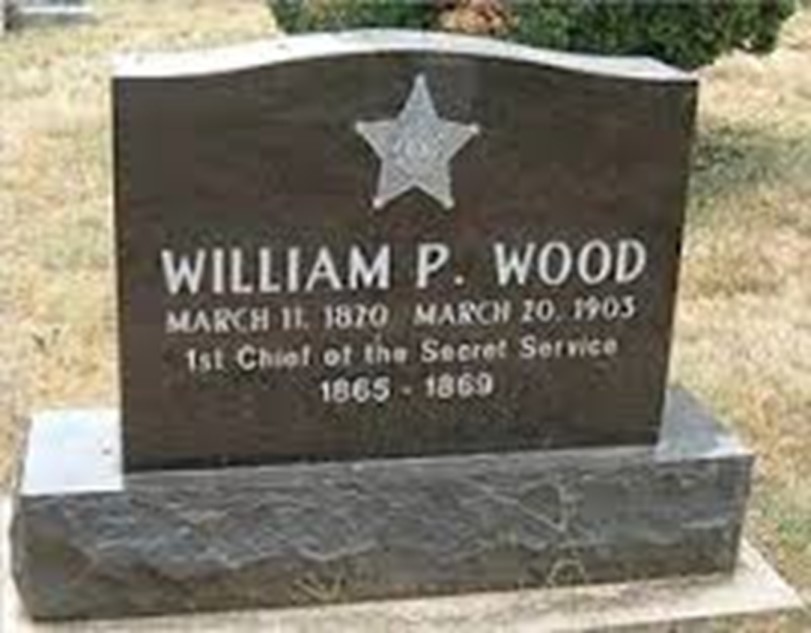

Resigning in 1869 when the new president took office, Wood published a column for a few years on law enforcement issues as a detective and spent much of the rest of his life trying to get paid the thousands of dollars he believed he was truly owed by the Government. Rutherford B. Hayes signed a letter agreeing that we owed him the money but nobody ever paid him. The $15,000 shortfall today would be worth millions, but my son Ryan and I have decided that it is unlikely that we will ever see a dime of it. William P. died poor in 1903 at 83 and did not have the money for a proper burial for wife Harriet in 1897.

The good news is that the Secret Service decided to put up a proper tombstone honoring him in 2001. One of his admirers (Thomas Conrad, Confederate Army Captain and spy) at the eulogy said about William P. Wood, “With noble impulses, generous nature, and deep convictions, he never submitted to a wrong himself and never inflicted one on another.”

Written by Robert M. Wood 4 June 2020